Preached (via Zoom) on Sunday, 9 August, 2020, the Tenth Sunday After Pentecost, at All Saints Anglican Church, King City, Diocese of Toronto.

Readings:Genesis 37:1-4,12-28; Psalm 105:1-6,16-22; Romans 10:5-15; Matthew 14.22-33

They said to one another, "Here comes this dreamer. Come now, let us kill him and throw him into one of the pits; then we shall say that a wild animal has devoured him, and we shall see what will become of his dreams.” (Genesis 37.19-20)

Would you want to be known as a dreamer? I suppose the answer would depend on the type of dreams. If they were wooly headed, Walter Mitty type dreams of escape and fantasy, then I doubt that any of us would take being called “dreamer” as a compliment. But, if the dreams were idealistic, of a better world, then we might well be pleased to be thought of as a dreamer, because some of the greatest men and women of history have been dreamers and visionaries. So that would be ok, to be a dreamer in a good way, unless … you had to be a price for being a dreamer.

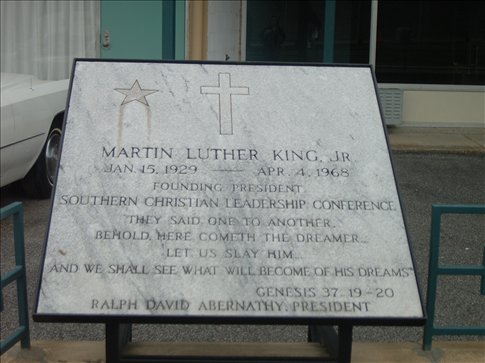

Dreamers often pay a price for their dreams. Go to Memphis, Tennessee, outside the Lorraine Hotel, where Dr. Martin Luther King was murdered, and you’ll see a plaque quoting our first lesson from Genesis, “They said to one another, “Behold, here cometh the dreamer, let us slay him and see what will become of his dreams”. Today the Lorraine Motel is part of the US National Civil Rights Museum, marking an achievement but no a victory. The street protests since the murder of George Floyd this summer show us that King’s dream is still very much alive, if not fully realized.

The story of Joseph in Genesis is also a story of dreams and a dreamer that cannot be suppressed. It’s a story of how God can turn the worst of human impulses to the good. It begins as another instalment in the troubled family story of Abraham and his descendants, which as we have seen is a story full of rascals, deception, and intrigue.

Here the hatred of his brothers to Joseph seems to be provoked by their father Jacob’s favouritism of his youngest son, which threatens their future security and power. Joseph however does not help his cause by telling his brothers of two dreams (Gen 37.5-11) in which the older brothers seem to honour the youngest. So the brothers, annoyed and jealous, at first plan to murder Jospeh, but in the end settle for a living death by selling him into slavery and deceiving their father into thinking him dead.

Even with these last minute scruples, the brothers’ actions are a shocking act of betrayal in a culture where family honour and loyalty to kin are everything. Their actions are also shocking because the brothers belong to the family of Abraham, the family that God chose be a blessing to the world (Gen 12.2, 22.8). How could any blessing or goodness come from such a family? You might think that God might scrap his plan at this point and find a more promising vehicle for his blessing than these rascal sons of their rascal father Jacob, but that’s not how God works. Instead, God chooses to work through Jospeh.

As you may know, either from Genesis or the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical, Joseph’s dreams continue. His dreams will earn him his freedom and the favour of Pharaoh, they save Egypt from famine, and allow Joseph to rescue and forgive his brothers at the end of the story. The story of Joseph and his dreams is ultimately a story about how God works in the midst of human affairs, as messy and sordid as they may be, because God’s dream for us is always a dream of justice, forgiveness, reconciliation, and new beginnings.

God’s dream is of a world that is worth cherishing and protecting because it is God’s gift of creation to all its inhabitants. God’s dream is of a human family where all are loved and all are equal because all our cherished children of God, regardless of skin colour. God’s dream is of love that heals, love that sacrifices itself, love which forgives even from a cross. God’s dream is of life that conquers fear, hatred, and even death itself.

God’s dream for us comes in many forms, across the ages. It comes in scripture, it comes in eloquent voices that can never be silenced, like Dr. King. God’s dream comes to us in simple acts of service and kindness, in moments of forgiveness and grace. God’s dream comes to us in quiet moments when we allow ourselves to hear that still, small voice.

God’s dreamer’s may pay a price for speaking of this dream, because not everyone wants to hear it, but God’s dream is always worth sharing, and always finds new dreamers. God’s dreams are the church’s dreams. We are called to dream with God. We are called to share God’s dream with others. The church is like a a sleeper who wakes each day, who remembers God’s dream, and who takes that dream with her into the light of every new day.

No comments:

Post a Comment