9He also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt: 10“Two men went up to the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector. 11The Pharisee, standing by himself, was praying thus, ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other people: thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even like this tax collector. 12I fast twice a week; I give a tenth of all my income.’ 13But the tax collector, standing far off, would not even look up to heaven, but was beating his breast and saying, ‘God, be merciful to me, a sinner!’ 14I tell you, this man went down to his home justified rather than the other; for all who exalt themselves will be humbled, but all who humble themselves will be exalted.”

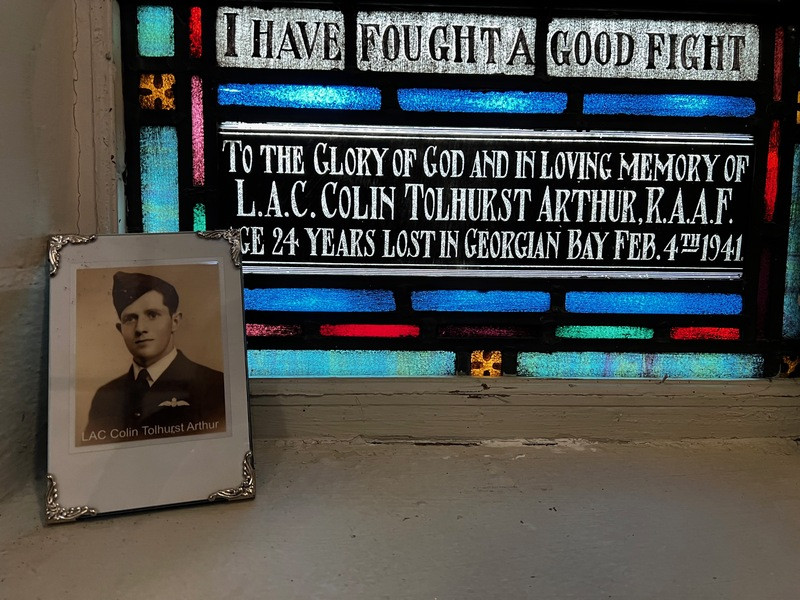

Preached at All Saints Church, Collingwood, Anglican Diocese of Toronto. Readings for this Sunday: Joel 2:23-32; Psalm 65; 2 Timothy 4:6-8,16-18; Luke 18:9-14

He also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt:

Can you be a good person without God? I sometimes heard this question from the young soldiers I spoke to when I was a military chaplain. I tried to be very careful in my answer because our experience tells us that it’s complicated. We all know non-believers who are kind, decent people. We’ve also known religions people who can be awful people, like the Pharisee in today’s gospel lesson.

1The Pharisee, standing by himself, was praying thus, ‘God, I thank you that I am not like other people: thieves, rogues, adulterers, or even like this tax collector.

When I hear people talk about why they’ve abandoned the Christian faith, one of the most common reasons I hear is the hypocrisy and hatred of some believers. There’s a widespread impression that Christians are intolerant, judgemental, and self-righteous, particularly around issues of sexuality, race, immigration, and politics. It’s not a good look for the church.

Luke also understood this tendency of religious people to be self-righteous. He even offers a sort of Coles Notes to guide our interpretation of Jesus’ story: “He also told this parable to some who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt” (Lk 18:9). It’s not just that the Pharisee compliments himself and despises others, which is bad, but the Pharisee, we are told, “trusts in himself”, which is worse.

Which brings me back to the question, “Can someone be good without God?” When I have this conversation, I try to explain that this question doesn’t really make sense to Christians, because we believe that can’t really separate the idea of goodness from God. St. Paul in Romans says that goodness comes from God (he uses the word diakos which is usually translated as righteousness - for our purposes today we’ll just call it “goodness”). Paul goes on to say that Christians as believers try to submit to God’s goodness, meaning that we try to understand it and live it out in our daily lives (Rom 10.3).

The Christian life is a way of life made possible because of God’s goodness. We know that God is good because God creates us, and because God sent his son to love us, to teach us, and to save us. The Christian life, then, is a response to God’s goodness. One can be good without God, but to try that is rather like listening to a radio station that isn’t properly tuned in. The signal is faint and full of static. When we synch our lives with God’s goodness, then we know what the good life looks like.

And what the good life looks like? One way to understand the good life is to ask, does how I live please God? This question is not unlike the bumper sticker slogan, “What Would Jesus Do”, and it’s a question that much occupied the mind of Paul and others who wrote the parts of the New Testament we call the Epistles. Paul fo example writes

Finally, then, brothers, we ask and urge you in the Lord Jesus, that as you received from us how you ought to walk and to please God, just as you are doing, that you do so more and more (1 Thes 4.1)

So how do we please God? If I was doing a children’s focus, I’m sure I’d get some good answers to this question, because children have an innate grasp of these things, whereas we adults try to be impressive and theological. If I asked a child how we please God, the answers might include:

Be kind to others and help them

Share what you have

Say your prayers

As adults, we might flesh this out a bit more, for example, we please God by volunteering in the church and in the community, by forgiving others or seeking their forgiveness as necessary, by tithing or giving to good causes, by being true to our wedding vows, etc. In articulating a life pleasing to God, we would be drawing on our understanding of the Ten Commandments, the Sermon on the Mount, the more pastoral epistles such as James, and a whole body of Christian ethics. Or we could sum the idea of a life pleasing to God in the words of our liturgy. As we used to pray according to the Book of Common Prayer:

OUR Lord Jesus Christ said: Hear O Israel, The Lord our God is one Lord; and thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it: Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. (BCP pp. 68-69)

I wonder, for those of us who have said those words often for much of our lives, if we ever took them as seriously as they deserved. To love God “with all we have - in our hearts, in our thoughts, in our willpower, in the depths of our souls - to give all those things to God. It’s hard to imagine a higher calling, it’s hard to think of greater demands. How few of us, if indeed there are any of us, who have risen to that calling, and yet there they are, in our old prayer book, and the prayer book took it from the gospel (Luke 10:24-28). Which brings us to the Pharisee, because, this is the very same calling, these are the same demands, that the Pharisees of Jesus day accepted.

Now here I think we need to stop for a second and check our prejudices at the door. How many of us have heard sermons about how Jesus rejected the religious legalism of the Pharisees in favour of an authentic faith based on love and kindness? I’m sure I’ve preached such a sermon, which causes me much regret, because as Christians we often have stereotyped, even hostile views of Judaism.

It’s largely true that in Luke, the Pharisees are painted negatively as adversaries of Jesus, who practice hypocrisy and loved wealth. This portrayal probably stems from Luke’s writing for a largely gentile audience. In fact, the Pharisees of Jesus time were famous for shunning wealth, and for taking the laws of God as found in the Torah with the utmost seriousness. The Pharisees’ ideal was to live a life which, by scrupulously following the law of God, would be pleasing to God.

I don’t think I ever really understood Judaism until my last year of military service, when a young Orthoodox rabbi named L was assigned to my padre team in Borden. L was a new recruit, and he wanted to work hard, subject to the limits of his religious beliefs. He would not carry the duty phone on weekends, because the Shabbat, the sabbath started Friday evening and ended on Saturday evening, a time when he could not do any work. This caused some grumbling among my Christian padres, who felt that, thanks to L, they had to work weekends more often.

Our training cycle started in the fall, but since most of the Jewish high holidays are in September and October, that didn’t work for L and we had to go to some lengths to work around him. As Christians we had crosses and images of Jesus and Mary in our offices, and we frequently met in a chapel, which, as L gently explained to us, was offensive to him, since orthodox Jews don’t look at human images.

So there was a LOT of adjusting that we Christians had to make to be respectful of our Jewish colleague, but over time I realized the deep sincerity and faithfulness that L brought to the table. Obeying God and pleasing God were just part of his DNA, as natural to him as breathing, and I came to admire the way his faith was part of every moment of his life. Which brings me to the Pharisee in Luke.

There’s nothing wrong with his religious practice per se. In our gospel reading today, the Pharisee’s declaration that he fasted twice a week and gave away a tenth of his income may have been seen as exaggerated piety, rather like Ned Flanders in the Simpsons is a comic representation of Christians. But that’s not the problem. What’s deeply offensive is his smugness. His faith is narcissistic, it’s not really based on God at all. He looks on those around him, like the tax collector, with contempt, and he measures his goodness (diakos) but what he sees as its opposite (adikia) in those who he sees as spiritual riff-raff.

So what of the tax collector? Has he lead a life pleasing to God? Obviously not, because here he is, beating his breast in repentance, not even daring to look at heaven, and asking only for mercy. It’s widely thought that as a tax-collector, he would have been a collaborator for the Romans and their puppet kings. He would have been seen by his contemporaries the same way that patriotic Ukrainians today would see one of their own wo worked for the Russian occupation. He hasn’t been a good man. So why does he go away “justified”? Why does God forgive him?

First, he’s where he needs to be. As we heard in the words of the psalmist, “Our sins are stronger than we are, but you will blot them out. Happy are they whom you choose and draw to your courts to dwell there!” (Ps 65:3-4). The tax collector has come to task forgiveness right there, in God’s court. Second, his very act of repentance is pleasing to God. In his parable of the Lost Sheep, Jesus says that “there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous people who need no repentance” (Lk 15.7). One of the most profound lessons of the gospel of Luke is that it pleases the Father most when the lost children come home. If you doubt me on this, then I encourage you to re-read the parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32).

Was the tax collector a good man? He comes to God thinking he’s not. He calls himself a sinner. He throws himself on God’s mercy, and Jesus tells us that he leaves a “righteous” (diakalos) or a good man. How did he become a good man? He became a good man because of the goodness and mercy of God, in the same way that we become good people. The tax collector knew one thing that the Pharisee didn’t; he knew that goodness comes from God.

I started off with asking if we can be good without God. As Christians, it’s not a question that makes sense. Without God we can be kind, or nice, or charitable, but all of those ideas are deeply rooted in Christian teaching and ethics. As Christians, we believe that goodness ultimately comes from God, and since it is God who makes us good, we can arrive at goodness from several directions. We can seek goodness like the tax collector, on our knees, in a spirit of repentance, trusting only in God’s mercy. Or we can seek goodness from a spirit of zeal as the Pharisees of Jesus’ day actually did, dedicating our whole lives, heart, soul, and mind, living according to God’s will.

Chances are it will be a bit of both. Some days will be saints days and some will be sinners days. There will be saints days when we strive to devote ourselves to knowing and doing the work of God. Those will be good days. There will be sinners days when we doubt that there is any good in us and we throw themselves on the mercy of God in Christ. Those will also be good days. The only bad days when we decide that goodness comes from within us, and so we fall into self-righteousness and judgementalism. May God, from who all goodness comes, spare us from such days and from such error, so that all are days are good and so that we are good all our days.