(This week was especially busy, and after preaching last night, I decided to find a sermon from three years ago, which had pretty good bones, but needed a new intro and conclusion. So apologies to longstanding readers of this blog who may find this somewhat familiar. Also, it was fascinating to reflect on the pandemic time we were in three years ago when I first wrote this, and how far we have come since then, gratia deo! MP+)

Preached at All Saints, Collingwood, Anglican

Diocese of Toronto, 18 February, 2024.

Readings for this Sunday: Genesis 9.8-17, Psalm

25.1-9, 1 Peter 3.18-22, Mark 1.9-15

“He was in the wilderness forty days, tempted

by Satan; and he was with the wild beasts; and the angels waited on him.” Mark 1.13

This verse from today’s gospel reading, told in

Mark’s typically laconic style, feels like a test or preparation, doesn’t it?

It reminds me somewhat of films or books

about someone preparing to do something heroic, who must first learn a skill

and prove themselves.

Think of Rocky

preparing for a big match in the ring, or Luke Skywalker learning how to use

the force, or the Soldiers in Band of Brothers going through basic training

before going overseas to fight.

The fact that the synoptic gospels all begin with the

temptation of Jesus in the wilderness makes me think that something similar

might be going on in the gospels. It

seems as if Jesus can’t begin his ministry until he proves himself in some way,

and the importance of this time of testing is underscored by some significant

details.

The testing occurs in the wilderness, where the

Israelites wandered and where they didn’t do very well (that whole golden calf

episode, for example). Jesus is tested

for forty days, which is one of those

significant numbers in scripture - Moses

led the Israelites in the wilderness for forty years, the early church saw

Jesus as a new Moses who would save God’s people. Our church calendar also points to the

importance of forty: Lent is forty days

from Ash Wednesday to Easter and it’s a traditional time to fast like Jesus and

think about our faith, our mortality, and our dependence on

Jesus.

I think that because we associate Lent with some

kind of privation and personal sacrifice, and because the temptation stories in

the gospels are always heard on the first Sunday of Lent, we can conclude that be

Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness somehow it explains Lent. I

don’t think it has anything much to do with “Jesus suffered for forty days, so

we can give up chocolate to honour his sacrifice”, which is how I’ve sometimes

heard it explained. What I want to do today is think about how

the start of Lent helps us understand who Jesus is, what he does, and why we

follow him, and I think today’s gospel reading is a good place to dig into

that.

Now it may seem as if we’ve been stuck in the

opening chapter of Mark for weeks now. We heard the baptism story a

few weeks ago, and you may be wondering why we’re going back to it

today. There are three events in today’s gospel:

1) Jesus is baptized and identified as God’s son

2) Jesus is tempted in the desert

3) Jesus proclaims the kingdom of God

Mark doesn’t tell us why (1) or (2) are

necessary. They just happen. Mark’s whirlwind

storytelling style is to throw events at us and leave us to make sense of them

as best as we can, but they all seem connected.

A few weeks ago I spoke about the baptism of Jesus

– I talked abut how Jesus shows God still engaged in God’s work of creation –

that Jesus’ baptism in the Spirit shows us a new way of being in which we can

be God’s children by adoption, to be God’s beloved sons and

daughters. Fair enough, but why is Jesus then immediately sent

to the wilderness? In Mark’s telling, the Spirit “drives” (the Greek

word is ekballo, which can mean “to thrust” or “expel”) Jesus into

the wilderness – it’s an urgent verb which suggests a crisis or an emergency.

So what is this all about? If it is a

test, why does Jesus have to be tested? Is God not sure of his

ability? Considering that the voice from heaven has already

named Jesus as “my Son, the Beloved” (Mk 1.11), I don’t think Jesus has

anything left to prove. Rather, I think Jesus goes to the

wilderness to confront something. The wilderness as Mark

describes it is a place of spiritual extremes – angels are there, but so is

Satan , and the beasts are wild, suggesting something that is untamed and even

deadly. Mark suggests that Jesus must go to the

wilderness to confront something.

Typically, Mark doesn’t say anything about how that

confrontation went. There is no climactic, Hollywood style

battle. Sometime after these forty days, Jesus replaces John

the Baptist, who has been God’s messenger, and announces the coming of the

kingdom of God and the need to repent and put trust in the good

news.

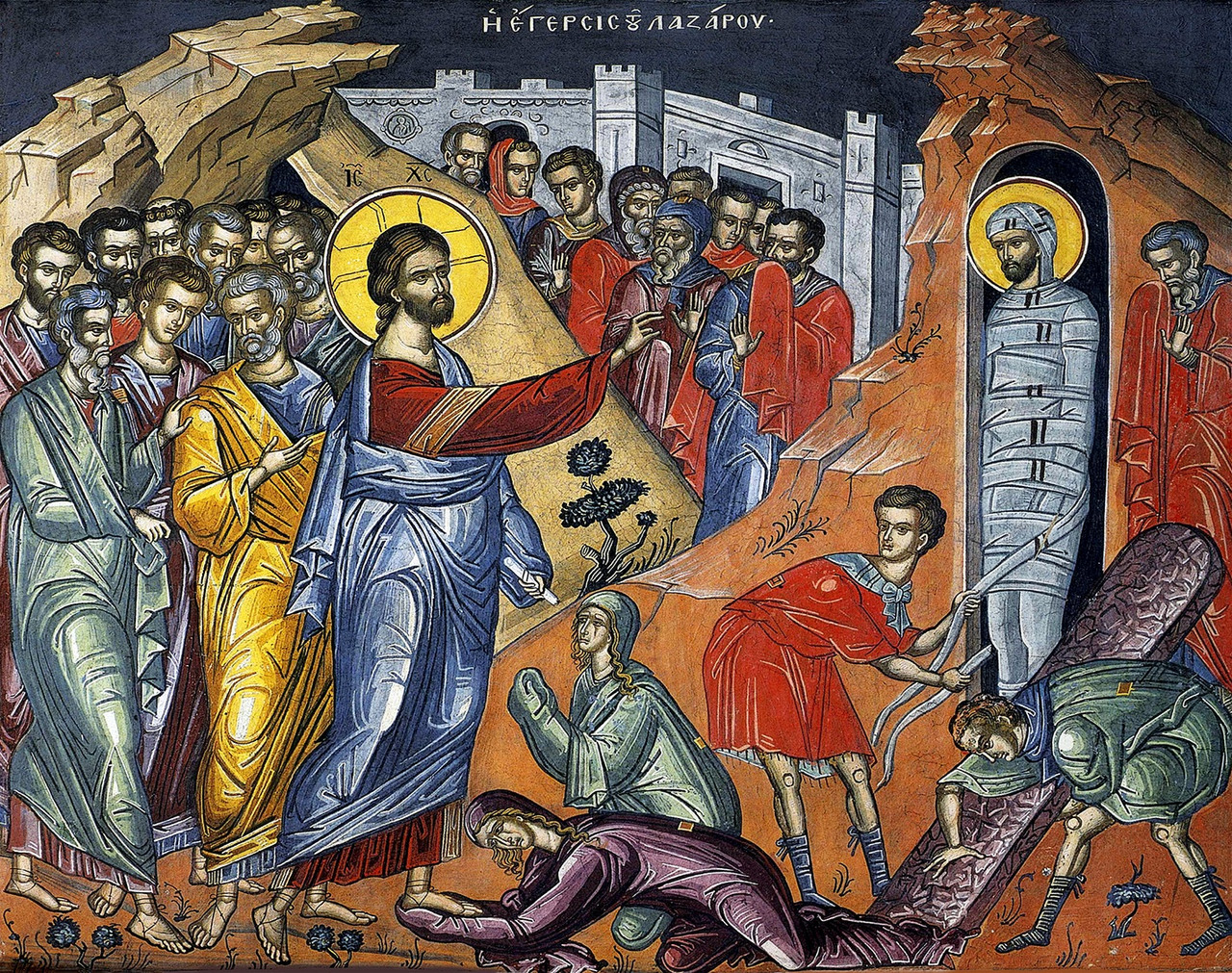

Next, to show us what the kingdom of

God, we see Jesus curing people and driving out victims (Mk 1.21-34), and the

demons screaming with the knowledge that Jesus has come to destroy them

(1.24). The kingdom of God is thus revealed as healing, life, and

freedom from the things that oppress the people of God. Mark does

not make the connection explicitly, but it seems that the confrontation between

Jesus and Satan in the wilderness prepares Jesus to face sin and death. If

Jesus is tested, then, it’s not see if he is sinful, but more like being tested

in the way that a weapon is tested.

And what a curious weapon God forges in the wilderness. Demons

fear him, even his disciples fear him when they see him transfigured, but whole

towns bring him their sick. Jesus’ power will be shown in acts

of compassion and healing. Just as angels served him in the

desert, so will serve others. As Jesus says “the Son of Man came not

to be served, but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many” (Mk

10.45).

Here is the lesson of Mark, that Jesus goes into

the desert to confront Satan to show God’s love for us. Jesus

demonstrates the Father’s love by rescuing us from sin and death, by taking our

place on the cross. God tried to defeat sin with raw power once, and

that didn’t work so well.

Our first lesson reminded us of the Flood story in

Genesis, which, whatever you think about it’s historicity, is a story about the

problem of evil and how God ultimately chooses to address

it. In promising never to destroy the people God has made, God

decides to find some other way to deal the evil things that offend his perfect

sense of justice.

God’s decision to save Noah, his family, and their

descendants is, if you like, a parable showing that God commits to seeing his

great project of creation through to a happy end and a grand

conclusion. God, who has the power to create and destroy the

earth, resolves instead to save humanity because the whole story of scripture

tells us that God is, first and foremost, love. In the Flood, God

tried to use power to get rid of sin and evil and it nearly destroyed

humanity. Now, God will use love instead. That’s why the

journey of Lent leads to the cross, because to save us, God must give himself

in our place. That’s how love works.

Lent has traditionally been a somber time in which

the faithful are urged to reflect on our sins and to express our penitence in

acts of sacrifice and austerity. I was looking back at some of the

Lenten sermons that I preached during the height of the pandemic, and I was

reminded of how much that felt like a wilderness time, making sacrifices,

living with fear and isolation. Austerity is our daily

lot. Lent during Covid became a way of life. We had a lot

of time to think about what we had been forced to give up.

Now that things seem more or less back to normal(ish),

I propose that this Lent we dedicate

ourselves to gratitude. We can be especially thankful for the business

of our parish life, for our ministries and friendships. We can be thankful for our communities and

for the ways we are called to contribute to them. We can be

thankful for the little rituals that give our days and our lives.

If there is a spiritual practice that you want to

rediscover, then try thinking back to the pandemic, when we were less busy and

had more time for stillness, more time to listen for God’s voice that speaks

most clearly in silent moments. Let’s

try to be more attentive to the friendship God offers us in Jesus, who emerged

from the wilderness greater than any action hero. Let’s meditate on the fact that the God’s

great love and power came together in the one who was proven ready to save us,

while at the same time befriending us and inviting us to walk with him.