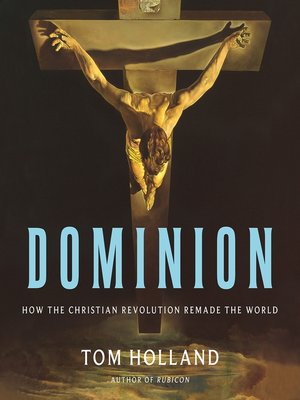

I’m currently reading Tom Holland’s book, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World (New York: Basic Books / Hachette, 2019). Holland is book is religious history, written by an outsider with some knowledge of Christianity, but it is not theology. Nevertheless, I found this description of Paul’s gospel message to be both brief and a compelling summary of Paul’s own theology. MP+

To an age which - in the shadow first of Alexander’s empire, and then of Rome’s - had become habituated to the yearnings of a universal order, Paul was preaching a deity who recognized no borders, no divisions. Paul had no ceased to reckon himself a Jew; but he had come to view he marks of his distinctiveness as a Jew, circumcision, avoidance of pork, and all, as so much ‘rubbish’. It was trust in God, no a line of descent, that was to distinguish the children of Abraham. The Galatians had no less right to the title than the Jews. The malign powers that previously had kept them enslaved had been routed by Christ’s victory on the cross. The fabric of things was rent, a new order of time had come into existence, and all that previously had saved to separate people was now, as a consequence, dissolved. “There is neither Jew not Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus”.

Only the world turned upside down could ever have sanctioned such an unprecendented, such a revolutionary, announcement. If Paul did not stint, in a province adorned with monuments to Caesar, in hammering home the full horror and humiliation of Jesus’ death, then it was because, without the crucifixion, he would have had no gospel to proclaim. Christ, by making himself nothing, by taking on the very nature of a slave, had plumbed the depths to which only the lowest, the poorest, the most persecuted and abused of mortals were confined. If Paul could not leave the sheer wonder of this alone, if he had risked everything to proclaim it to strangers likely to find i disgusting, or lunatic, or both, then that was because he had been brought by his vision of the risen Jesus to gaze directly into what it meant for him and for all the world. That Christ - whose participation in the divine sovereignty over space and time he seems never to have doubted - had become human, and suffered death on the ultimate instrument of torture, was precisely the measure of Paul’s understanding of God: that He was love. Paul, in proclaiming it, offered himself as the surest measure of its truth. He was nothing, worse than nothing, a man who had persecuted Christ’s followers, foolish and despised; and yet he had been forgiven and saved. “I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me."

And, if Paul, then why not everybody else?

No comments:

Post a Comment