Preached at All Saints, Collingwood, Anglican Diocese of Toronto, Easter Sunday, 31 March, 2024. Isaiah 25:6-9; Psalm 118:1-2, 14-24; Acts 10:34-43; John 20:1-18

Jesus said to her, "Woman, why are you weeping? “

(Jn 20.13)

There are times in our lives, mercifully rare, we hope, when despair and grief are too much for us, and our only recourse is to weep, and by weep I mean something more than a sad sniffle. Weeping is a word that we use to describe what we sometimes call, in today’s vernacular, “ugly crying”, when our faces crumple and distort and inarticulate sounds come from deep within us, hence the phrase “weeping and wailing”. I’ve seen soldiers, strong men and women, weeping at the sight of a comrade’s flag-draped casket. To truly weep is to find one’s self in a place of utmost despair.

It is in such a place that we find Mary Magdalene in our

Easter gospel reading. John doesn’t

tell us why she has come to Jesus’ tomb in the predawn, though we can imagine

what she saw and felt, standing near the cross as Jesus died along with her hopes. Perhaps she had hoped that in visiting his

tomb, she might find some comfort and companionship there, in the way that grief

brings us to the gravesides of loved ones.

But Mary finds no comfort, only the confusion of an empty

tomb and the indignity of a stolen body, which she reports to the disciples. It’s only after they see for themselves and

leave that Mary begins to weep. John

tells us that “As she wept, she bent over to look into the tomb” which may mean something more than “she was

curious and had another look”; rather it

may imply that she in her sobbing she had doubled over or crumpled to the ground

and only then did she see the angels. Even

then her grief persists, because Jesus (whom she does not recognize) asks her

again, “why are you weeping” (Jn 20.13).

“Why are you weeping” is

the question that undergirds the miracle of Easter. It is the question that Jesus likewise asks

as we stand, confused and uncertain, beside his empty tomb. “Why are you weeping?”

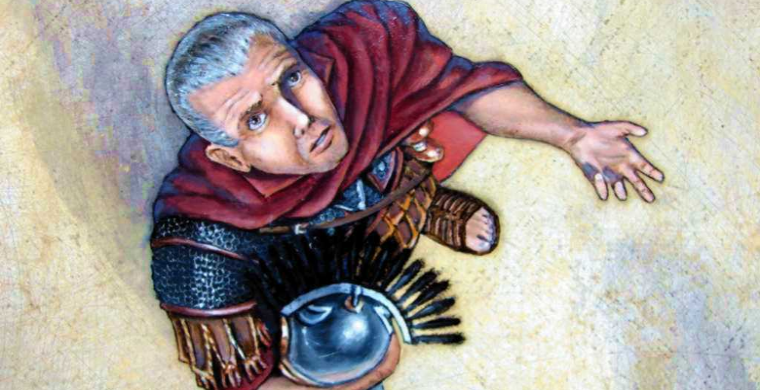

Why are we weeping? We are weeping because we, like Mary, have been

weeping since we saw our Lord taken in the garden. We have wept for his betrayal by his

friend. We have wept to see an innocent

man cruelly killed. We have wept for

ourselves, because we cried out “Give us Barrabas” and “Crucify him”, because

we promised to stick with him till the end, until we abandoned and denied

him. We have wept for our sins which

Jesus took to the cross to be bought and paid for. We have wept and we still weep for the world

which God so loved, and which we have imperilled in so many ways.

Why are you weeping? It seems to me that we as a society are

either weeping, sad, or just laughing nervously because we find ourselves, like

Mary Magdalene, in a place of grief, confusion, and hopelessness. Last week in The Guardian, Dorian Lynskey

wrote a piece on our current dystopian

mood called “End of the World Vibes”.

Lynskey he noted that “A

peer-reviewed 2021 survey of people aged between 16 and 25 around the world

found that 56% agreed with the statement “Humanity is doomed” and that one

in three Americans expect an apocalyptic, world-ending event in their

lifetimes. This mood is fuelled by books,

streaming shows and films about zombies, pandemics, and environmental collapse. While Lynskey notes that doomsayers have

always been around, the current mood, and the fading of religion to the margins

of our society, mean that we are living through a crisis of hope. Many smart and caring people I know just

avoid the news these days, and those who are addicted to social media use a

word, “doomscrolling”, which means going from one moment of horror and outrage

to another.

It is to us, and to those

of us fearful or just numbed by this crisis of hope, that Jesus comes and asks,

“Why are you weeping?” It is a question

put to us with the greatest sympathy and understanding, for Jesus asks this

question with great sympathy, because he has never been afraid to weep. John tells us that Jesus wept and was “greatly

disturbed” at the grave of Lazarus, even though God would give him the power to

raise his friend from the dead (Jn 11:35,38).

In Luke’s gospel, as Jesus sees Jerusalem

for the last time, he weeps for the city, for its faithlessness and for its

impending destruction (Lk 19.41-45). In

the Garden of Gethsemane, Luke doesn’t tell us that Jesus wept for himself, but

his anguish and sweat “like great drops of blood” suggest something very close

to weeping. So of course Jesus asks Mary

why she is weeping because he understands what it means to weep. He understands the human condition because he

shared it fully, all the way up to death.

Such sharing and solidarity was the same point of the incarnation.

Likewise, the point of the resurrection is that the raising of Jesus from the dead means the end of our weeping. Nothing less than the resurrection can solve crisis of hope and end our tears. As he does with Mary, Jesus calls us to rise from our crouching posture, to get up from our fear and despair and sadness, to look into his face and see again our Lord and friend. Imagine Jesus gently brushing your face and wiping away your tears. Notice the wounds in his hands as he does so. Those wounds are there for us.

As Isaiah said,

“by his stripes are we healed”. Today

promises us that we are loved and forgiven. Being loved and forgiven does solve wars or save the planet, though it is a start. What it does mean is that we are not doomed. It means that we as followers of Jesus can do our part for God's kingdom while facing whatever befalls us with peace, knowing that doom and death have no dominion.

The risen Jesus is the end of our weeping. Indeed, the final story of the Bible, the climax of the Christian story, is the abolition of weeping.

‘See, the home of God is among mortals.

He will dwell with them;

they will be his peoples,

and God himself will be with them;

he will wipe every tear from their eyes.

Death will be no more;

mourning and crying and pain will be no more,

for the first things have passed away.’

(Rev 21:3-4)

God does not promise us a life free from pain. There will be times for tears, as there was

in our Lord’s life. But today is the

assurance that hope and life have triumphed over despair and death. Today is the beginning of the end of all our

weeping.