Preached on Sunday, November 26, 2023, at All Saints, Collingwood, Anglican Diocese of Toronto, on the Last Sunday after Pentecost: The Reign of Christ.

Readings - Ezekiel 34:11-16, 20-24; Psalm 100; Ephesians 1:15-23; Matthew 25:31-46

Today in the life of the church and in our church calendar is called the Feast of the Reign of Christ. It’s a day that invites us to think of the authority of Jesus Christ over our lives, our church, and our world.

“Reign of Christ”. The word “reign” is a verb, meaning to exercise power and authority as a monarch. As a noun, “reign” means the dates between when a monarch is crowned and, typically, when they die. Thus, the reign of Queen Elizabeth II was from 1952 to 2022.

As Christians, a day called “The Reign of Christ” begs some questions. Has Christ’s reign started, or will it begin on some future date when, as today’s gospel promises, ‘When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory” (Mt 25.31)?

What will the reign of Christ look like? What sort of authority will Jesus have as our king? Do we even want Jesus to be a king, given that we have so many other ways of thinking about him, as friend, as brother, as radical or revolutionary. There are many ways of thinking about Jesus, and not all of them align neatly with our human ideas about power and authority.

For us as 21st century Christians living in a democracy, we may have trouble conceiving of Christ as a king because terms like monarchy and reign are archaic and may even have negative connotations. What does a monarch look like today? How do we recognize one?

It may be an odd question to those of you here today who are ardent royalists. Of course we know what King Charles looks like, because he’s deeply familiar to us as a celebrity. Tabloids, Netflix series, and the like have the British royals duly familiar to us, if not all deeply revered. We recognize them as people, but how do we see their authority (such as remains) in a confusing and increasingly disordered world where postmodernity has made the idea of authority deeply suspect.

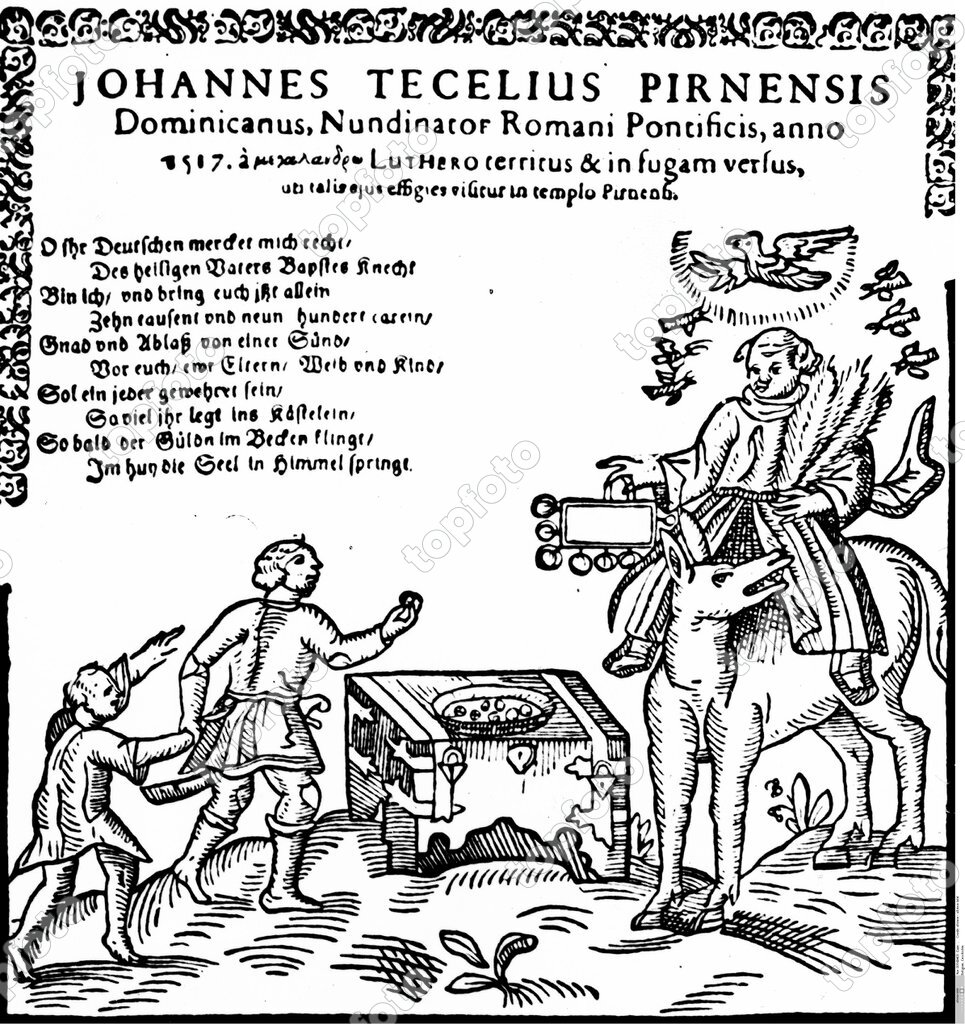

In the ancient world, kings and emperors were distant figures, and few of their subjects would have known them by sight. Thus, coins were used symbols of authority, each bearing the likeness of the ruler and showing his power by a crowned or wreathed head. Coins spoke of an earthly authority that Jesus never claimed.

You may remember how, when Jesus was asked about paying taxes, and asked for a coin, he pointed at the image of Caesar and said “Give therefore to the emperor the things that are the emperor’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (Mt 22.21). Jesus cleverly implied that the emperor’s human authority had limits within and beneath the authority of God his Father.

Likewise, when Pilate asks Jesus if he is a king, Jesus points to a different reality and a different understanding of authority: “My kingdom is not from this world”, Jesus says (Jn 18.33-38). When Jesus is convicted and killed, his crown of thorns and the inscription on the cross, “The King of the Jews”, are mocking gestures of contempt, but perhaps they also show traces of fear, an awareness that there is an unworldly kingdom that will ultimately judge the kingdoms of this world.

And he will judge them, as our gospel reading promises:

32All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats” (Mt 25.32).

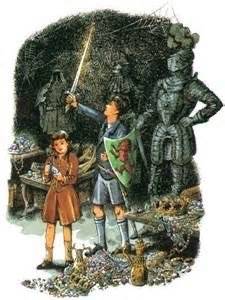

Matthew’s does promise that Jesus will come again as king and judge, and in that respect, today’s gospel functions as a yellow highlighter, underscoring these words of the Creed: “And he shall come again with glory to judge both the quick and the dead”. Matthew imagines Jesus as a king returning in glory, surrounded by angels, in the tradition of Jewish apocalyptic prophets like Daniel, so the glory is there in full view, but the underlying authority, the underlying values of the kingdom, are not obvious at first.

Matthew imagines that on the day of judgement, even the righteous will be puzzled.

Then the righteous will answer him, “Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food, or thirsty and gave you something to drink? 38And when was it that we saw you a stranger and welcomed you, or naked and gave you clothing? 39And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?” (Mt 25:37-39)

They are puzzled because Christ the King was with them all along. He was the hungry and thirsty stranger, he was the cold person shivering in rags, he was the prisoner. The king’s crown was his poverty, the king’s throne was the piece of cardboard on the pavement. The King was there all along, and while nobody recognized him, the righteous were the ones who bothered to show love and care to him and to the least amongst them.

And if the King was there all along, when did the king’s reign begin? The King’s reign began in service. Earlier in Matthew, two disciples, James and John, want the best seats in God’s kingdom, on either side of Jesus. Don’t think that way, Jesus scolds them. That’s gentile thinking, he says; their rulers lord it over them as tyrants. Jesus says that his kingdom is built on service.

“whoever wishes to be great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be your slave; just as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many.” (Mt 20:26-28).

The Reign of Christ begins in every action of love and charity. Christ the King is seen in the faces of those whom we might otherwise pass by and ignore. Christ the King is served at the tables of our Friendship Dinners and in the hot meals our Five Loaves team sends out the door. Christ the King is served by those agencies who receive Faith Words funding, and my thanks to you for dedicating part of our recent Pub Night proceeds to Faith Works.

Today, as we prepare our hearts for Advent, we pause to understand better the King and Saviour whose coming we eagerly expect. We recognize that our King’s authority is not always understood by the rulers of this world, and is sometimes feared by them, for that authority rests on love and willing service, values that tyranny and coercion will never overcome. We know our King because he does not lord it over us. Jesus calls us friends and invites us to follow him. We wait for him, but we know that he is already here, in the ones we are called to serve, and in serving them, we help show Christ’s kingdom to the world.