Where clashed and thundered unthinkable wings

Round an incredible star.”

Nor thorns infest the ground;

He comes to make His blessings flow

Far as the curse is found,

Far as the curse is found,

Far as, far as, the curse is found.”

I'm Michael Peterson, a priest in the Anglican Church of Canada, currently serving a parish in the Diocese of Toronto. I'm also a retired Canadian Forces chaplain , hence the Padre in the title. Mad just means eccentric, and on that note, I also blog on toy soldiers, madpadrewargames.blogspot.com. I'm on X (what used to be Twitter) at @MarshalLuigi and I'm on Bluesky at @madpadre.bsky.social

|

We gather today on this hallowed ground on

which is interred Canada’s Unknown Soldier, to remember all those who made

the ultimate sacrifice. On the Centennial of the signing of the Armistice, we

honour those whose names we know, and those whose names are known to God

alone.

For those of you who wish to

join me in prayer,

in the respect of our freedom

of religion, I invite you to turn your hearts to the God of your

understanding or to take this moment in personal reflection.

Please

join me in prayer or in a moment of personal reflection.

(Choir

starts humming I vow to Thee my country until the end of the prayer)

Loving

God,

We give thanks for those who have given their lives in the

service of justice and peace.

We

know that peace is more than tolerating one another, it is recognizing

ourselves in others, and realizing that we are all on the path of life together.

Lord of peace and justice, enable us to lay

down our own weapons of exclusion, intolerance, hatred, and strife. Make us

instruments of your peace that we may seek reconciliation in our world.

As

we remember those who returned from past wars with injuries, both visible and

invisible, inspire us to care for all military personnel who are wounded in body, mind, and soul.

Help us to have compassion for our brothers and

sisters, who, for reasons known and unknown, have considered or attempted

suicide. May we be compassionate for the

families and friends impacted by these tragedies.

We remember the families,

friends, comrades, and caregivers of those who, in time of war and peace,

have paid the ultimate sacrifice to restore peace. Be their refuge and

strength in moments of grief

We pray for all military

members who are deployed around the world in dedication to the welfare of

humanity, and the preservation of justice and peace. Inspire them to give

their best in the cause of freedom.

We pray for our Sovereign

Lady, Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada, for the Governor General, the Prime

Minister, our Chief of Defence Staff and all in authority: that they may have

the wisdom, and compassion to meet the call of their offices.

On this Centennial year of the Armistice,

we remember and pay respects to our fallen by answering their call to peace.

In sure and certain hope, we

pray.

Amen.

|

Nous sommes réunis

aujourd’hui en ce lieu sacré où repose en paix le soldat canadien inconnu,

pour nous rappeler de tous ceux et celles qui ont fait l’ultime sacrifice. En

ce jour du centenaire de la signature de l’armistice, nous voulons rendre

hommage à ceux et celles dont nous connaissons les noms et ceux et celles

dont les noms sont connus de Dieu seul.

Dans le respect des croyances individuelles, j’invite toutes les personnes qui

veulent se joindre à moi dans la prière à tourner leur cœur vers le dieu de

leur foi ou à prendre un moment de réflexion personnelle.

Je vous invite à vous joindre à moi dans la prière ou prendre un moment de réflexion personnelle.

(La chorale commence à fredonner I vow to Thee my

country jusqu’à la fin de la prière)

Dieu d’amour,

Nous te rendons grâce pour

ceux et celles qui ont donné leur vie au service de la justice et de la paix.

Nous savons que la paix c’est plus que tolérer l’autre; c’est se

reconnaître dans les autres, c’est

réaliser que nous sommes tous ensemble sur le chemin de la vie.

Dieu de justice et de

paix, aide-nous à laisser tomber nos propres armes d’exclusion, d’intolérance,

de haine et de conflits. Fais de nous des instruments de ta paix afin d’apporter

la réconciliation dans le monde.

Alors que nous nous

rappelons ceux et celles qui ont été marqués par des blessures, visibles ou

invisibles, inspire-nous de prendre soin de tous nos militaires qui ont été blessés

dans leur corps, leur esprit et leur âme.

Aide-nous à être plein de

compassion à l’égard de nos frères et sœurs qui, pour des raisons connues ou

inconnues, ont envisagé ou tenté de se suicider. Rends-nous sensible à la souffrance des

familles et des amis touchés par ces tragédies.

Nous nous souvenons des familles, des amis, des

collègues et du personnel soignant de ceux et celles qui, en temps de guerre

et de paix, ont fait le sacrifice de leur vie pour restaurer la paix. Sois leur soutien et leur force dans

les moments de deuil.

Nous prions pour tous les militaires déployés autour

du monde, dévoués au mieux-être de l’humanité et à la promotion de la justice

et de la paix. Inspire-leur de donner le meilleur d’eux-mêmes pour la cause

de la liberté.

Nous prions pour notre souveraine, Sa Majesté Elizabeth

II, Reine du Canada; pour la gouverneure générale, le premier ministre, le

chef d’état-major de la Défense et toutes les personnes en autorité; que la sagesse

et la compassion les accompagnent dans l’exercice de leurs fonctions.

À l’occasion de cette

année du centenaire de l’armistice, nous nous souvenons et rendons hommage à

nos disparus en répondant à leur appel à bâtir la paix.

Dans cette espérance, nous te prions.

Amen.

|

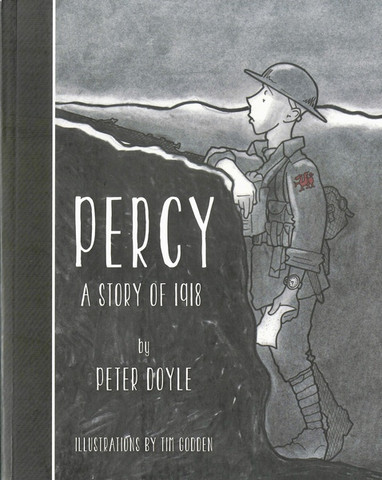

In my previous post I mentioned the British artist Tim Godden, who specializes in images of the Great War and of Edwardian sports figures. His style captives me - there’s a simplicity and a sincerity about it I prefer to the legions of commercial artists out there specializing in military scenes. Tim excels at capturing the humanity and vulnerability of his subjects, as in his collaboration with Peter Doyle, Percy: A Story of 1918.

I wanted a portrait of Phillip Clayton, one of the most well-known British chaplains of the Great War. An Anglican, “Tubby”, as he was widely known, was not one of the front-line chaplains like F.R. Scott or Geoffrey Studdert-Kennedy (Woodbine Willie) but his greatest service to the troops was to found and run Talbot House, a sort of hostel not far behind the line in the Ypres Salient, in the town of Poperinge. Talbot House, or “TocH” as it was known in the phonetic signaller’s alphabet of that war, was mostly a refuge, though it was within reach of enemy artillery. Clayton wrote that “During the varying fortunes of the Salient shells have crossed and recrossed the roof from three points of the compass at least”.

Here is Godden's depiction of Clayton. I will keep the original, and will donate a print of it to the Chaplain School of the Royal Canadian Chaplain Service before my tour here ends.

What made TocH special was its all ranks nature. Clayton had a sign prominently displayed, “ALL RANK ABANDON YE WHO ENTER HERE”. Tim has placed the sign at the top of the painting, and has Tubby framed in the door of his office. Figures of the soldier guests can be seen in the mirror behind him.

The Talbot House motto allowed an informality and companionship that was otherwise seldom possible in the socially rigid and stratified Army of the day. Here is an excerpt from Clayton’s book, “Tales of Talbot House”.

Under its aegis unusual meetings lost they awkwardness. I remember, for instance, one afternoon on which the tea-party (there generally was one) comprised a General, a staff captain, a second lieutenant, and a Canadian private. After all, why not? They had all knelt together that morning in the Presence. “Not here, lad, not here”, whispered a great G.O.C. at Aldershot to a man who had stood aside to let him go first to the Communion rails; and to lose that spirit would not have helped to win the war, but would make it less worth winning. There was, moreover, always a percentage of temporary officers who had friends not commissioned whom they longed to meet. The padre’s meretricious pips seemed in such a case to provide an excellent chaperonage. Yet further, who knows what may be behind the private’s uniform? I mind me of another afternoon when a St. John’s undergraduate, for duration a wireless operator with artillery, sat chatting away. A knock, and the door opened timidly to admit a middle-aged Royal Field Artillery driver, who looked chiefly like one in search of a five-franc loan. I asked (I hope courteously) what he wanted, whereupon he replied: “I could only find a small Cambridge manual on paleolithic man in he library. Have you anything less elementary?” I glanced sideways at the wireless boy and saw that my astonishment was nothing to his. “Excuse me, sir,” he broke in, addressing the driver, “but surely I used to come to your lectures at ____ College.” “Possibly,” replied the driver, but mules are my speciality now.

You can compare Godden’s likeness to this period photograph of Clayton.

Talbot House is now a museum and a hostel, and can be visited by tourists. I hope to make a pilgrimage there myself in the foreseeable future.

I have some more excerpts from Tales of Talbot House, now sadly out of print, that I hope to post here as time permits, as they are excellent stories and vignettes of military chaplaincy from the Great War.

MP+

Percy: A Story of 1918, by Peter Doyle with illustrations by Tim Godden. London: Unicorn Publishing Group, 2018. ISBN: 978-1-911604-81-5

Percy is a collaboration between a distinguished British historian of the Great War, Peter Doyle, and illustrator Tim Godden to tell the story of a young lad who left his life in a coal mining village in Wales to serve in the infantry in the final year of the War. It is a true story, told thanks to the discovery of the young man’s letters to his sweetheart Kitty, which turned up years later in a flea market.

While aimed at older children and young adults, I thoroughly enjoyed Percy. The first chapters make an accessible social history of what life was life in the coal pits of Edwardian Britain. Suffice to say that the men and boys who went into those mines required just as much courage as they would have needed to face the trenches. It was a dangerous and dirty life, and Doyle tells the story with realism and sympathy while never sliding into sentiment.

We then follow Percy into the Army as a volunteer, wanting to do his bit like his brother and the other men of his village. Doyle takes us through the disorientation of his training and deployment to France, all the while comforted by letters to and from his sweetheart Kitty. The tale is told with great empathy not only through Doyle’s words but through Tim Godden’s wonderfully vivid watercolours. Godden is a noted artist, specializing in the Great War and in sports figures of the early twentieth century. there isa wonderful charm and simplicity to his work, and it is perfectly suited to this project.

I won’t tell you how the book ends, except to say that I found it immensely powerful and moving. Percy Edwards was just one of millions of boys and men caught up in that vast conflict, and in this little book Percy becomes a kind of Everyman, speaking for all of them.

Percy: A Story of 1918, is available on Amazon. I ordered mine from Amazon UK, and it took a while getting to me in Canada, but it was worth the wait.

MP+

Preached at St. Margaret of Scotland Anglican Church, Diocese of Toronto, Barrie, ON, 21 October, 2018, the Twenty-second Sunday after Pentecost

Texts: First Reading) Job 38:1-7, Psalm 91:9-16; (Second Reading) Hebrews 5:1-10, (Gospel) Mark 10:35-45

“

whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant, 44 and whoever wishes to be first among you must be slave of all. 45 For the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many.” (Mark 10:44-45)

Last week I was at a conference of my fellow military chaplains, and a familiar complaint was raised. “What do I have to do to get promoted?” “Why was so and so promoted after only a few years, while other good chaplains work hard but are still not promoted?” “I would like some recognition for the good things I do.”

The ironic thing was that these complaints came after a discussion that focused on our common mission as chaplains and officers: caring for military members and their families, looking out for subordinates, and generally being true to our chaplain corps motto, “Called to Serve”.

You can see the contradiction quite clearly. Here are a group of religious people who are trying to live out a common vocation of service to others. At the same time, as members of a military system that uses rank and medals to measure seniority and prestige, these caring and selfless people also cared about themselves.

I’m not surprised, therefore, when James and John come to Jesus and ask to share in his glory. Sure, they sound like a couple of shallow numbskulls, but their behaviour is hardly unusual among the disciples. Just a bit earlier in Mark’s gospel, Jesus hears the disciples arguing and bickering as they are walking along. When he asks them what the argument was about, they shuffle their feet and awkwardly admit that “they had argued with one another who was the greatest” (Mk 9:34).

After that episode, Jesus told the disciples that “Whoever wants to be the first must be last of all and servant of all” (Mk 9:35). Nevertheless, here are James and John, just one chapter later, asking Jesus to be seated beside him in what they think is his heavenly glory. So yes, James and John may be especially obtuse in not understanding the kind of kingdom that Jesus is offering, but I don’t think they’re alone. I think of my chaplain colleagues, wanting to serve others but also wanting to make Major or Lieutenant Colonel, and I see a bit of James and John in them. It’s a bit of a contradiction, the call to selfless service and the need for recognition.

Surely this is a contradiction that most church people can relate to. I think we understand selflessness at some level because we are schooled in it by our life in the church. As children we hear chancel step talks about being nice to others. We sing hymns like “Sister let me be your servant”. We hear scripture readings like today’s gospel, which check our ego and tell us that “whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant” (Mk 10:43).

Nevertheless, our egos stubbornly refuse to remain in check for long. We like to be recognized. Lots of clergy delight in getting titles like Canon. Clergy and lay people like to be thanked at Synod for their service on committees and projects. Congregations are grateful when the Bishop comes and tells them they are doing a good job. Remember the last time that Bishop Peter came here and told us how proud he is St. Margaret’s and the work we do as a parish? That made us feel pretty good, didn’t it? The desire for acknowledgement and recognition is pretty universal in the church, because it’s a human desire, and churches are made up of people.

Parishioners, being people, like to be recognized for all their various ministries. A simple shout out from the priest during the announcements — “Thanks to all the hard work of Jane and Jim, our yard sale raised XX dollars” — carries a lot of weight. And why shouldn’t we thank people? I learned early on as a priest that two of the most effective words I could say in the parish were “Thank you”.

In the ancient world, in the courts of the rulers and tyrants that Jesus mentions in Mark’s gospel, no one said “thank you” to a servant. Servants and slaves were meant to be efficient but invisible, only noticed if needed, like so many household appliances. We say “thank you” to acknowledge service and express gratitude. It’s a way of saying, “I see what you did there, I noticed how hard you worked, and I’m grateful for it.” Every Sunday I’m grateful for all the ministries that make our worship happen, for the leadership that keeps the parish running, and for all the selfless giving of money that keep Simon paid and the lights on and the doors open. I know that you don’t do these things for fame or glory, but I still want to say thank you, to all of you, for all that you do.

In the two years I have been here, I often look around at this parish and think, “Wow, this is a great place. We could do some things better, but we really get being church, and we do it well. Is it wrong to think that? Is it prideful to think that all of this talent and energy and selflessness makes St. Margaret’s a special church? Is it wrong to want St. Margaret’s to harness all of its potential, to want it to be a leader and a role-model for other Anglican churches in this part of the Diocese? Yes, I suppose it would be misguided pride, if we wanted these things solely for the gratification of our egos. It would be certainly be wrong if we thought that God loved us for being such a good church. Because, really, God just loves us. Regardless.

The whole point of church is to bring people together to rely on the love and grace of God. That’s it. Our second lesson from Hebrews makes this point well. The author of Hebrews reminds us that even the priest, yes, even Simon and me and everyone else at the front, relies on this love and grace just as much as every person in the pews. Hebrews says that the priest, “is subject to weakness” and must therefore “offer sacrifice for his own sins as well as for those of the people” (Heb 5:2-3). All of us, even the folks in the fancy white robes, are imperfect. None of us could not stand before God if it wasn’t for God’s love and willingness to set aside our shortcomings.

Everything good that we do as a church is because of God’s love in Christ. Everything important that we should do as a church going forward is because of God’s love in Christ. Hebrews says that Christ is “the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him” (Heb 5:9). If we take pride in St. Margaret’s as a parish, it should be because we bring people to relationship with Christ. If we make plans for St. Margaret’s to grow, or to improve, or to build a new wing of our building, then Christ should be at the centre of our plans.

There is nothing wrong taking pride in our parish, or feeing good when Bishop Peter tells us that we’re doing a good job. There’s nothing wrong with finding satisfaction in our various ministries to make it all happen. It’s very human to want to be seen and recognized for our contributions, whatever they may be. Some of us are at places and stages in life where we need to be helped and served by others in the church, and that’s okay. Others of us have gifts and talents and energies to serve as Christ calls us to serve. All of us can say thank you. All of us can say I’m glad you’re here. All of us say how can I help. When we do and say these things, we will look around, and we will certainly see Christ in our midst. A church with Christ in its midst is certainly a church, well, not to be proud of, but to be grateful for.