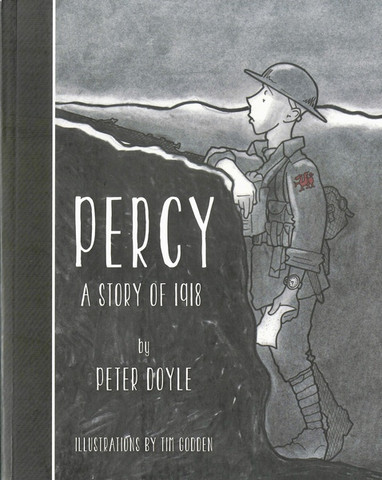

In my previous post I mentioned the British artist Tim Godden, who specializes in images of the Great War and of Edwardian sports figures. His style captives me - there’s a simplicity and a sincerity about it I prefer to the legions of commercial artists out there specializing in military scenes. Tim excels at capturing the humanity and vulnerability of his subjects, as in his collaboration with Peter Doyle, Percy: A Story of 1918.

I wanted a portrait of Phillip Clayton, one of the most well-known British chaplains of the Great War. An Anglican, “Tubby”, as he was widely known, was not one of the front-line chaplains like F.R. Scott or Geoffrey Studdert-Kennedy (Woodbine Willie) but his greatest service to the troops was to found and run Talbot House, a sort of hostel not far behind the line in the Ypres Salient, in the town of Poperinge. Talbot House, or “TocH” as it was known in the phonetic signaller’s alphabet of that war, was mostly a refuge, though it was within reach of enemy artillery. Clayton wrote that “During the varying fortunes of the Salient shells have crossed and recrossed the roof from three points of the compass at least”.

Here is Godden's depiction of Clayton. I will keep the original, and will donate a print of it to the Chaplain School of the Royal Canadian Chaplain Service before my tour here ends.

What made TocH special was its all ranks nature. Clayton had a sign prominently displayed, “ALL RANK ABANDON YE WHO ENTER HERE”. Tim has placed the sign at the top of the painting, and has Tubby framed in the door of his office. Figures of the soldier guests can be seen in the mirror behind him.

The Talbot House motto allowed an informality and companionship that was otherwise seldom possible in the socially rigid and stratified Army of the day. Here is an excerpt from Clayton’s book, “Tales of Talbot House”.

Under its aegis unusual meetings lost they awkwardness. I remember, for instance, one afternoon on which the tea-party (there generally was one) comprised a General, a staff captain, a second lieutenant, and a Canadian private. After all, why not? They had all knelt together that morning in the Presence. “Not here, lad, not here”, whispered a great G.O.C. at Aldershot to a man who had stood aside to let him go first to the Communion rails; and to lose that spirit would not have helped to win the war, but would make it less worth winning. There was, moreover, always a percentage of temporary officers who had friends not commissioned whom they longed to meet. The padre’s meretricious pips seemed in such a case to provide an excellent chaperonage. Yet further, who knows what may be behind the private’s uniform? I mind me of another afternoon when a St. John’s undergraduate, for duration a wireless operator with artillery, sat chatting away. A knock, and the door opened timidly to admit a middle-aged Royal Field Artillery driver, who looked chiefly like one in search of a five-franc loan. I asked (I hope courteously) what he wanted, whereupon he replied: “I could only find a small Cambridge manual on paleolithic man in he library. Have you anything less elementary?” I glanced sideways at the wireless boy and saw that my astonishment was nothing to his. “Excuse me, sir,” he broke in, addressing the driver, “but surely I used to come to your lectures at ____ College.” “Possibly,” replied the driver, but mules are my speciality now.

You can compare Godden’s likeness to this period photograph of Clayton.

Talbot House is now a museum and a hostel, and can be visited by tourists. I hope to make a pilgrimage there myself in the foreseeable future.

I have some more excerpts from Tales of Talbot House, now sadly out of print, that I hope to post here as time permits, as they are excellent stories and vignettes of military chaplaincy from the Great War.

MP+