Preached at St. Coliumba’s Anglican Church, Remembrance Day Sunday, November, 2014

Three weekends ago I happened to be in Ottawa, near Parliament Hill. I’d been told that there was an honour guard of Canadian Armed Forces members at the National War Memorial and I wanted to have a look at them. I was not disappointed. Two young soldiers, immaculately turned out in their dress uniforms, stood at attention at the base of the tall stone pillar, beneath the larger than life bronze statues of soldiers from their great-grandfather’s war. A young private, a Reservist from the Nova Scotia Highlanders, stood a short distance away, ready to speak to the public. I asked him some polite questions about the purpose of the ceremonial guard. In clipped, professional tones, he told me it was part of the 100th anniversary of the start of World War One, and that the guards were drawn in turns from the Army, Navy, and Air Force. As we talked, another soldier played a lament on the bagpipes. Tourists grinned happily while they took each other’s pictures with the soldiers in the background. I complimented the Private from Nova Scotia on a job well done, and left. As I walked away, I wondered if that young Private was old enough to shave.

Four days later we learned that one of those young honour guards lay crumpled and dying at the base of that monument. He was Corporal Nathan Cirillo, a handsome young man with a winning smile, a dog and a little son. He died two days after another soldier, Warrant Officer Patrice Vincent, was mowed down by a car. Both were singled out and killed because they were wearing the uniform of their country. In both cases, the attackers were mentally unstable loners who used jihadist language but appeared to have the sketchiest understandings of Islam. For several days, the country held its breath until we realized that this was not an organized plot, and that we had no reason to fear our Muslim neighbours and fellow citizens. In Alberta, in the Air Force town of Cold Lake, when someone sprayed hate graffiti on the walls of a mosque, members of the community pitched in and helped clean it up. Some of those who helped wore military uniforms. Canadian values of acceptance and pluralism (I won’t say tolerance because that is a stingy, miserly word) held firm. My boss, the Chaplain General of the Canadian Forces, joined with Muslim and Jewish leaders at the Anglican cathedral in Ottawa for an interfaith service called Prayers for Ottawa. In the ways that matter, Canada came out of this week more itself than ever.

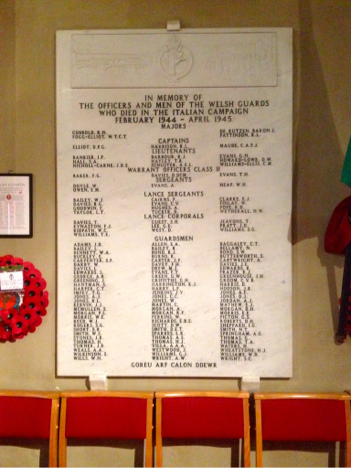

In one respect, however, Canada has changed. I think it will be a long time before any of us wear a poppy casually. Perhaps there was a time when we wore the poppy out of habit. Perhaps we saw a young Cadet with a poppy box outside Zehrs and thought, “Oh yes, it’s that time again.” I think this year we will take the poppy more seriously. The poppy reminds us that all those names carved in stone, all those names from our grandparents wars, belonged to real people. As John McRae wrote of the dead nearly a century ago, “We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, loved, and were loved”. If you have, like me, been following the weekly column in the Record on Kitchener-Waterloo residents who died in the First World War, you will know what I mean. All of these young men (and some women) in those stories left real families and real jobs, and real houses, some of which still stand today. They never came home. Patrice Roy and Nathan Cirillo, or the 157 young men and women lost in Afghanistan, are no different from the dead of Korea, of Dieppe, or of Passchendaele. They were all real people. Cartoonist Bruce McKinnon put it well the day after the Ottawa shooting, when he drew the image of bronze statues climbing off the War Memorial to raise the body of Cpl. Cirillo into their ranks.

As a soldier and as a chaplain, I’ve wrestled with quite a few emotions since these events. As a soldier, I’m proud of people like Roy and Cirillo. The four values of the Canadian Forces are Courage, Loyalty, Duty, and Integrity, and these two men seem to have lived these values right up to the end. However, as a chaplain, I struggle with our instinct to reach too high on occasions like this. At Nathan Cirillo’s funeral, someone said that he died at the most sacred spot in Canada, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. It is certainly sacred in that it is a consecrated site, an actual burial place. However, beyond that, I think we need to be careful about how we apply the word sacred to the War Memorial and what it stands for. I think we need to take care that we don’t say that these deaths were pleasing to God, and I don’t think, frankly, that as Christians we can say that. The young men who left jobs as clerks and farmers in Waterloo region to go to Flanders in 1914 were told that they were fighting for God, King and Country. The young Germans they fought were told the same thing, and they wore belt buckles on their uniforms on which were stamped the words “Gott Mitt Uns” (God With Us). In some cases, those young Waterloo men and their foes in the other trenches spoke the same language and may even have been related, because, as you know, Waterloo wasn’t called Waterloo in those days. It was called Berlin. I don’t see how God could have taken sides in that war. I just can’t see it.

I have a friend, a bright young officer, who asked me once why chaplains don’t pray for a good smiting. I asked him what he meant. He told me, “When I was in Afghanistan, before we went out on a mission, I wanted the Padre to pray for God to help us smite our enemies. No one did. I like Padres, but why can’t you guys pray for a good smiting?” Probably, I told him, because we can’t. If we did, then would we be any better than those who recruit suicide bombers and promise them a speedy trip to paradise if they kill in Allah’s name? I think that’s why my trade is the only one in the military that don’t carry weapons. Doctors and medics carry weapons to protect their patients. Clerks and cooks carry rifles because they may just get called on to fight. Chaplains don’t carry weapons of any sort. We’re not allowed to, and we wouldn’t want to if we could. There’s a story about a group of soldiers out marching somewhere, and their chaplain was with them. “Padre,” one said, “Why don’t you carry a rifle? That’s not normal.” Before the chaplain could answer, another one said, “No, you don’t get it. Carrying a rifle everywhere is not normal. The padre’s the only one who’s normal. He’s here to remind us what normal is.”

Most chaplains I know love this story because it speaks to who we are and why we’re there. Some say that we as clergy condone war and violence just because we wear the uniform. We don’t think we do. We think we are there to show God’s love to the men and women who have accepted their role, as hard as it may be for them. No soldier in their right mind wants to go fight and kill, but that is what they are trained to do, and that is what they are called to do by the country they serve. Soldiers, because of their profession, have to go to dark places that seem far from God, and that is why chaplains go with them, to remind them that God has not abandoned them. Many soldiers are touched and damaged by the brokenness they must face. Many struggle with addictions of various sorts. Their relationships are strained by long absences and many military marriages fail. Not all soldiers do the right thing. Some become coarse and brutal. Calling all soldiers “Heroes”, as society likes to do, does them no favours. They don’t call themselves heroes. They are ordinary people, and like you and me, they are sinners. That’s why we chaplains chose this ministry, because it’s full of broken people who need the assurance of God’s love.

Very few Canadians have any real connection with the military. Unless you live in a military town, chances are you don’t see people in uniform. It’s not the career of choice for bright young people who want money and comfort. However, as Anglicans, you have a connection with the military. The Anglican Church has over forty of its clergy in uniform, either part time or, like me, full time. Anglican chaplains are leant to the military by the Church. The Diocese of Huron supported me financially as a theological student, and then after I did four years of ordained service, Bishop Bruce Howe let me go to the military. In effect, he was writing off your investment in me. He didn’t have to, and not all bishops do, but he agreed that the military was a valid calling for me. General Synod gives us chaplains a Bishop Ordinary, who is currently Bishop Peter Coffin, a retired Bishop of Ottawa, and helps us pay him a small stipend, too small for all the work he does for us. When +Peter retires in a few years, General Synod has given us permission to elect our own Bishop Ordinary going forward. Many chaplains go back to the civilian church when they retire from the military. So in many real ways, you as the Church are connected to the Canadian Forces through the men and women you send to it as chaplains.

There was a time, long ago, when the Anglican Church just assumed that Canada should be a Christian country. The Church tolerated Roman Catholics and even Methodists, but really felt that all Canadians should be Anglicans. One of the reasons the Church sent clergy to the military was that we wanted to make soldiers more Christian, and preferably Anglican. Today my colleagues and I work with people of many faiths and, often, of no faith. If there’s an Anglican, or a Christian, who wants our services, we’re there for them. We’ll happily celebrate the Eucharist using the hood of a truck for an altar. But, if we meet a Jewish soldier who wants to celebrate Passover, or a Muslim whose sergeant won’t let him grow a beard, or a pagan who wants time off to celebrate the solstice, a chaplain will go to bat for those folks until they get what they need. As we like to say, we minister to our own, we help others get their faith needs met, and we serve everyone. We like talking to the “spiritual but not religious”, or to grizzled atheists and agnostics who say they would burst into flame if they ever set foot inside a church (so far, I’ve never seen this happen). We always try to show these men and women that God is with them, and sometimes we use words to tell them that. You as the Church can be proud of the work that your Anglican chaplains have done, and continue to do today, such as the work of Canon Rob Fead of the Diocese of Niagara, who served the Cirillo family in their time of grief.

Because you are the Church, and because you are connected to the military through your chaplains, and because you are Canadians, I think you have some responsibilities. You are called to think about God’s will and plan for humanity. Is war part of that plan? Can war and violence be justified? What does the cross say to us about the use of violence? What does the Resurrection say to us about death and life? What is the church called to say in times of war and violence? Do we speak in the name of a triumphant God who takes sides in human conflict, or do we follow a God who weeps for a broken world and calls it to peace and new life? These are issues that you the Church are called to wrestle with, and not just on Remembrance Day. Let me close by offering some suggestions to help you with these responsibilities. Pay attention to the news about places like the Middle East. Try to resist easy judgements and answers, and try to dig into the stories. Listen to different voices, such as the News Service on the Anglican Communion website, or even Al Jazeera. Support the troops but find out what they’re doing. Why are we sending troops and planes to the Middle East? What are Canada’s goas there? Are you hearing enough about these things from your elected leaders? While we’re talking about elected leaders, ask them what is being done for military families, for veterans young and old, especially those struggling with mental and physical injuries. Are you satisfied that enough is being done? Finally, as people of God, pray. Pray for peace, and pray for those who are called to bear arms in the absence of peace, and pray for my colleagues, chaplains of all faiths, who minister to our soldiers and their families.

Amen.